Yelvertoft Leatherlands

Yelvertoft Village

Yelvertoft is about a 20 minute drive from Rugby mostly along narrow country lanes. Although a small village it has a long wide high street approximately three quarters of a mile long. There is one pub, a small post office / general store, and – unusually for such a small village - a butcher’s shop. Yelvertoft was the home of my Leatherland ancestors mainly during the first half of the eighteenth century.

All Saints church is at the far end of the High Street on top of a small hill. It is slightly hidden from the road, being surrounded by trees and bushes. The church seems in good condition, with a large well maintained and attractive graveyard. A notice inside the church says that some of the graveyard has deliberately been left overgrown as part of a policy of encouraging wildlife.

Yelvertoft is very quiet and rural. The Grand Union Canal borders the village winding sleepily through the countryside a few minutes walk from the church. The canal turns a bend and passes under the High Street – the Yelvertoft tunnel – on its way to Crick.

The Reading Room dates from 1792 and used to be the village schoolhouse. There is a large sundial with the date above the door. It has a small tower on top which may have contained the school bell.

There is apparently a proposal to build a wind farm at Yelvertoft comprising 8 or 12 wind turbines between the village and the M1. The village was full of “NoWAY” (“No Windfarm at Yelvertoft”) posters.

Many of the fields between Yelvertoft, Clay Coton and the neighbouring villages of Lilbourne and Stanford on Avon, contain ridge and furrow field pattern remains, which is evidence of the medieval farming system and the largest surviving area of ridge and furrow fields in Northamptonshire.

Edward and Esther Leatherland

My direct ancestor EDWARD was the sixth son of Christopher and Sarah Leatherland. He was baptised in 1700 in Yelvertoft. In February 1726 he married Esther (or Hesther) Watts in West Haddon, a village three miles east of Yelvertoft. There was a Marriage Licence which described Edward the servant man of Jeremiah Bullock. There are several Jeremiah Bullocks who appear in the Crick parish registers during the 18th century. I think the licence says that Jeremiah was a schoolmaster. Edward executed the marriage licence by making a mark rather than by signing his name. Jeremiah Bullock was his name bondsman.

Why marry by license ? The usual way to marry was by the calling of banns, a public announcement of the intended marriage, three weeks before the wedding in order to give people the opportunity to object to the marriage. If the couple did not want to do this, they could marry by licence which was quicker and more discrete. A fee was payable for this which may have been thought to make the marriage more prestigious.

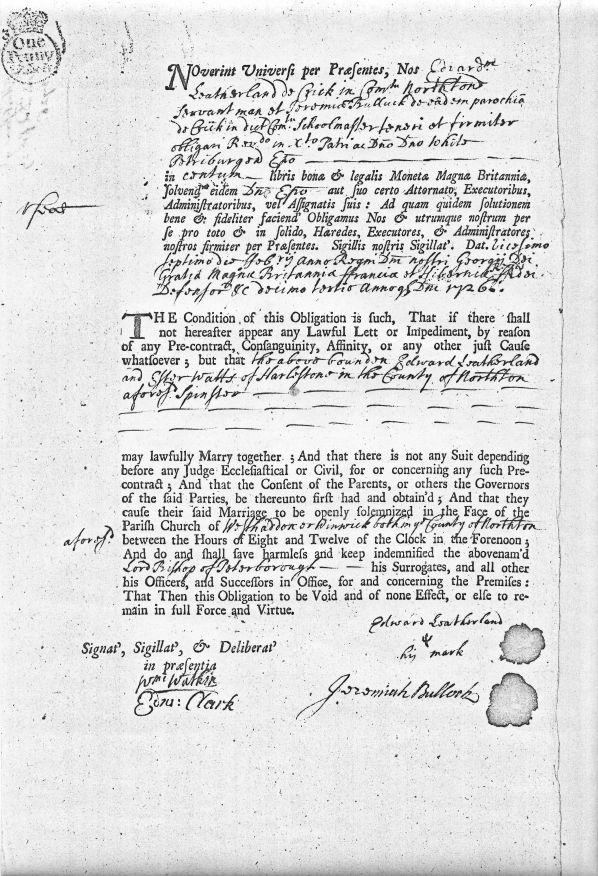

The document below is a copy of Edward's license from the archives of the Northants Record Office. Note that the existence of a marriage license does not actually prove that the marriage took place. Marriage bonds, which ceased to be required after 1823, were always divided into two parts. The first part, the obligation, was written in Latin until 1733 and noted the names and parishes of those bound (often including those of the bridegroom) and the amount of the penalty. The second part, the condition, outlined the terms under which a penalty would have to be paid (ie if the sworn statement proved to be false), and was always written in English.

Marriage Licence Bond of Edward Leatherland and his marriage to Esther Watts

We know quite a lot about Edward's wife Esther because her father, William Watts, left a will when he died in 1745. He was a carpenter who left his estate to Esther and husband Edward (described as a labourer in the will), to John Redgrave (carpenter), Martha (his daughter), John Ward (his son-in-law and a butcher), Elizabeth Sabin (a widowed daughter), and to Thomas Whitmell junior.

Edward and Esther had three boys baptised in Crick between 1732 and 1739. The first child was not baptised until they had been married for six years (which may indicate there were earlier children not yet traced). Edward was described as a labourer in the baptism entries. Their sons were :

- William baptised 1732 (who died aged 2)

- William baptised 1737

- Edward baptised 1739.

Edward Leatherland (senior) died in 1763 and was buried in Crick. Esther died in 1786.

John Laurence : Gardening Pioneer of Yelvertoft

“I do not know a more pleasing or healthful occupation than Agriculture and Gardening, occupations so compatible with the life of a Rural Clergyman.”

John Laurence was the Rector of Yelvertoft from 1703 to 1721. He was born in the 1660s in Stamford, the eldest son of a clergyman. He studied at Clare Hall, Cambridge in the 1680s and 1690s. He married Mary Groodwin, a vicar's daughter from Banbury.

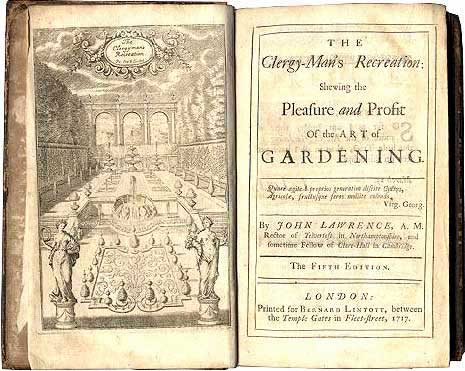

Laurence was a very keen gardener during his time at Yelvertoft and wrote a book called “The Clergy-Man's Recreation: Shewing the Pleasure and Profit of the Art of Gardening” first published in London in 1714. The book immediately became very popular and by 1717 it had entered its fifth edition. In 1718 he wrote another book “The Fruit-Garden Kalendar”.

Laurence's books were the first important books on gardening to be published in the eighteenth century. They became very popular. Copies were even bought by colonists in America. Laurence became a major figure in the history of English gardening. He was one of the first people to record the transmission of a plant virus by grafting. After leaving Yelvertoft in 1720 he became Canon of Salisbury 1720-32 and Rector of Bishopwearmouth in County Durham.

Susan Campbell's “A History of Kitchen Gardening" explains that Laurence's first act on moving to the rectory at Yelvertoft was to pull down part of the mud wall that enclosed a miserable weed-infested garden, and build a brick wall, nine feet high, for fruit.

The following appreciation of Laurence's work appeared in the Journal of Horticulture :

"To the close of the seventeenth century from the earliest period of Christianity its clergy were the chief promoters of the arts and sciences, and the authors and preservers of their literature. Gardening is not an exception to that rule. Gardeners in those times were totally illiterate, and to the clergy then living we are indebted for the only publications that imparted instruction in horticulture to their contemporaries, and that have preserved to us a record of their practice of the art. Of these clerical horticulturists the first of superior attainments known to us is the Rev. John Laurence, and anyone even now taking his ' Clergyman's Recreation ' and ' Gentleman's Recreation ' for his guides would not be led into faulty practice."