LEATHERLAND FAMILY BIOGRAPHIES

Here are some biographies of ancestors who interest and intrigue me.....

William Leatherland - the Grocer

William was born in 1845 in Pailton, son of Sarah Leatherland. His father is not known. He may have been brought up by his grandparents because the 1851 census shows him living with them in Monks Kirby, rather than with his mother who was a cook in an inn in Coventry. By the 1861 census William was a plough boy living as a boarder in Churchover with the family of James Lee, a farmer.

William married Sarah Lydia Baker in 1876. By then he worked as a provision dealer (shopkeeper) in Birmingham. The following year on his son, Charles' birth certificate, he was described a "cheese factor's salesman".

This photograph shows the interior of a late 19th century grocery shop. Grocers sold the essentials of daily life. Tea, flour, sugar and rice were stored in large containers, then weighed and wrapped for customers. Grocers also sold things like firewood and paraffin and, from the late 19th century, canned and processed foods such as condensed milk and processed fish. Grocers often lived above their premises. Late-night opening occurred on Saturdays when workers came to the shop after being paid.

My great uncle who was brought up in Birmingham, and who was a cousin of William, remembered William as the senior hand on the butter and bacon counter of a large grocer's shop in Birmingham city centre.

William and Sarah had three children, all boys. Two of his boys became acrobats and performers.

[A famous image of acrobats on the Empire State Building - this is NOT Will and Bertie Leatherland]

Will and Bertie Leatherland : Acrobats and Performers

My Grandpa and a Great Uncle told me that two of William the Grocer's sons became stage acrobats and performers, who performed under the stage name "Willbert and Lealand".

In the 1911 census they were enumerated under their stage names as Bert Lealand and William Wilbert, occupation acrobat and music hall artist. They were living in Manchester in a house which appears to have been a theatrical boarding house. Other residents included Richard Herzog (German theatrical artist) and his wife, Walter and Eugenie Hinchcliffe (musicians) and Joseph Sullivan (musician). The property next door had an actor, a music hall artist and a theatrical property master.

Immigration records provide evidence of their travels under their stage names "William Willbert" and "Bert Lealand". Bertie Lealand "artist" is listed in the "Manifest of Alien Passengers" arriving in New York in October 1910 on the ship 'Teutonic' which sailed from Southampton. Bert Lealand and William Willbert are both listed as arriving back in the UK on Christmas Day 1910 in Liverpool having sailed from New York on the White Star Line ship 'Arabic'. They appear in the immigration records again as Bert Lealand and William Willbert arriving in Liverpool from Brazil and Buenos Ares, Argentina on the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company ship 'Arlanza' in January 1915. On the passenger list they are described as actors. Another actor, James Curtis, was travelling with them.

Bertie served in the First World War. His military service record (under his real surname Leatherland) gave his civilian job as "taxi driver and interpreter". In 1920 he married Gertrude Saunders in Birmingham. They later settled in South Wales, Bertie making his living as a taxi driver. He died in 1961 in Glamorgan.

William died in Birmingham in 1926. His occupation on the death certificate was still "comedy acrobat".

William Leatherland - Gardener and "Champion Hedger and Ditcher"

(Copyright on this image is owned by Bob Jenkins and is licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/)

William was born in 1835 in Churchover. He was a cousin of my great x three grandfather Samuel Leatherland. In 1851 he was a 16 year old farm servant living in Ashby St Ledger, Northants in the household of Levell Cowley, a farmer of 304 acres who employed fourteen workers. The Cowleys were substantial land owners in the area for hundreds of years and even today some property in Kilsby remains under the ownership of Cowley family trusts.

William married Elizabeth Smart in Shearsby, Leicestershire at the age of 23. In 1861 he was living in Braunston, Northants working as a carter. In 1871 he was a labourer living near the George Inn, Kilsby with his wife and children. After that he seems to have remained in Kilsby and can be found there in the 1881, 1891 and 1901 censuses.

William and Elizabeth had a large family. They had sixteen children, including two pairs of twins. Sadly eight of their children died in infancy, including both pairs of twins.

Kelly's Directory of 1890 lists William Leatherland in Kilsby as a thatcher. The 1901 census says he was a gardener. A descendant described him as a "champion hedger and ditcher".

The former Rugby Poor Law Union Workhouse (photo © Ian Rob)

When William died in 1911 he was living in the Rugby Poor Law Union Workhouse. His wife Elizabeth had died the previous year. They had been married for over 50 years.

Although usually thought of as a Victorian concept, the workhouse continued in existence in the early decades of the twentieth century as a last resort for the poor. Why did William die in the workhouse ? Old Age Pensions had been introduced in 1908. A married couple would have received 7s 6d and William should have been entitled to a pension. But it may be that he entered the workhouse not so much because of poverty but because of illness. The 1911 census shows William still living in Kilsby with his daughters, Frances and Louisa. This census was taken six months before his death, so my guess is that he became ill in the last few months of his life, that his daughters found it difficult to care for him, and that this may explain why he ended the days in the workhouse.

The excellent www.workhouses.org website says that in December, 1906, a new 66-bed hospital block was opened at the south of the Rugby Workhouse which contained male and female wards on each floors, operating theatres on the ground floor, and seven nurses' rooms in an attic space.

Samuel Leatherland - Railway Worker

Samuel was born in 1874 in Kilsby, a son of William the gardener. In 1901 he was a 26 year old railway wagon cleaner boarding with the Taylor family (who all worked on the railway) in Rugby.

Samuel moved to London and married Emily Pfaff at the age of 38 in Willesden, London. The marriage certificate describes him as a painter. They had one son, Reginald, who lived in London and carried on the transport theme working as a London Transport booking clerk.

Railway workers

Samuel died in 1948. The death certificate said he was a railway labourer.

Robert Leatherland - Coal Miner in Nottingham

Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire are full of Leatherlands. Although my branch originated in Northants and Warwickshire, Robert is an example of an ancestor who was born and brought up in Northants but settled in Nottingham.

Robert was born in Kilsby in 1855, son of Samuel and Elizabeth. In the 1871 census he was a 16 year old agricultural labourer in Kilsby.

A late nineteenth / early twentieth century miner (Photo from the Cannock Chase Mining Historical Society website)

Some time during the 1870s Robert moved to Nottingham and became a coal miner. In 1878 he married Sarah Allen in Radford, Nottingham. He remained living in Radford and Nottingham. The 1901 census says he was also a main road contractor.

Robert died in 1922. His occupation was a coal miner contractor. Interestingly his son, who was informant on the death certificate, lived in the same road (Bobber's Mill Road, Nottingham) as one of my father's Richards ancestors although the two families were completely unconnected until my parents married in the 1960s. It's a small world.

Sarah Leatherland (nee Whiteman) - a Dairy Maid

Sarah's story is interesting. She was born in Kilsby in 1838, daughter of a labourer Thomas Whiteman who originally came from Leicestershire. In 1851 they lived in Crick. In 1861 she was a 23 year old dairy maid servant living with the Cowley family in Kilsby. The Cowleys were prominent farmers and landowners in Kilsby, in fact they owned 100 acres and half of all the land and property in Kilsby at this time. Sarah had a son James when she was 20. Two years later she had a daughter. There was no father named on the birth certificate.

This is a photo of a dairymaid (not Sarah) photographed around 1900 holding her luggie or milking-pail and her four-legged milking stool, the symbols of her occupation. Milking was always considered to be women's work. Dairymaids had an early start to the working day. Cows were milked twice, firstly at around 5 am and then at 5pm. In the nineteenth century milking the cows was carried out in the fields so the dairymaid would trudge out - often in darkness - across the fields with gallon buckets hanging off big wooden yokes which she carried across her shoulders. Cows are apparently sensitive animals who will often give more milk if they are milked by someone they know, so a dairymaid who usually stick to a certain group of cows within a herd and wear the same clothes or talk or sing to the cows to ensure they were recognised !

Milking a cow by hand is said to have been physically quite demanding, both on your hands and on your back as you needed to lean over to do it properly. An average cow produced one to two gallons of milk and when the buckets were full it was time to head back to the dairy. Dairymaids would often have to carry up to four gallons of milk - a substantial weight - and they had to be careful not to trip or stumble so as not to spill any milk. Once back at the dairy the milk would often be made into cheese or buttter. The dairy had to be kept srupulously clean and would be scrubbed daily with hot walter and salt.

[I am indebted to an article in Who Do You Think You Are Magazine Oct 2008 issue for this description of the life of a dairymaid].

Back to Sarah. When she was 30 years old Sarah married Samuel Leatherland, who was a 57 year old widower. They had a son, Henry, who later became a policeman in Northampton. I did wonder whether Samuel was the father of Sarah's first two children although they were not married at the time. Sarah's daughter, Annie Whiteman, became a domestic servant in Rugby. When married she named her father on the marriage certificate as William Poole. Presumably her mother told her about this.

Samuel died in 1894. The 1901 census shows Sarah as a 63 year old housekeeper living with a lodger Ann Bird. In 1911 census she was still living with Ann Bird. She died in Rugby Workhouse Infirmary of senile decay and exhaustion at the age of 78 in 1915. Her son Henry and his wife Violetta had six children all born in Northampton. Henry died of cancer a year after his mother.

In 2009 I made contact with the great grandson of Henry, Alan Webb, who lives in Northampton.

Samuel Leatherland - Brickmaker

Samuel Leatherland worked as a brickmaker in his early years. Before the late 18th century most houses outside large towns were built of materials such as stone, cob, or wood. Towards the end of the 18th century bricks started to be used to build houses and canal structures such as bridges and tunnels and - from the 1830s -railway viaducts, bridges and tunnels. This created a great demand for brickyard labourers.

The Kilsby Railway Tunnel was built in the hills near Kilsby between 1834 and 1838. It is 2,432 yards long and the tunnel walls used 30 million bricks. At the time it was the longest tunnel in the whole world. The tunnel formed part of the London to Birmingham railway line and now forms part of the West Coast Main Line from Euston to Birmingham / Manchester / Glasgow.

Gren Hatton's research on the history of Kilsby showed that - although there were no brickworks in Kilsby - there were two brickyards in the neighbouring village of Crick, one along the road to West Haddon (Foster's brickyard) and another along the south side of Watford Road.

The Grand Union Canal was opened through Crick in 1814, and it is likely that the bricks for the Crick tunnel and bridges were produced in Foster’s brickyard. The spoil heaps from the tunnel can still be seen next to the site of the old brickyard (later called Brick Kiln Close). The Watford Road brickyard closed after the First World War, and the brickyard buildings were demolished in the early 1930s.

It is quite likely that Samuel Leatherland worked at the Crick brickyards during the 1830s and 1840s and that one of his jobs was making bricks for the Kilsby railway tunnel.

Balcombe Railway Viaduct

In about 1839/40 Samuel and his family moved to Balcombe in Sussex. It is likely that he worked making bricks for the Balcombe railway viaduct. The Balcombe railway viaduct (known as the Ouse Valley viaduct) was built between 1838 and 1841 with 37 arches. It is 100 feet high and 1,500 feet long and its construction used 11 million bricks !!

We know about Samuel's stay in Balcombe because he appears there in the 1841 census. Living in the same household as Samuel and his family were three other men : 25 year old Joseph Foster, 20 year old Henry Waller, and 20 year old John Grimble. All three gave their occupations as clay labourer. Bricks can be made out of clay so it seems likely that they were working with Samuel. Waller said he was born in Sussex, but Foster and Grimble were both born outside the county. The census shows a large number of railways labourers living in Balcombe, many of whom were born outside the county, and many bricklayers..

Photo copyright FreeStockImages.org (see www.freestockimages.org)

An article by Philip and Dorothy Brown in the February 2008 issue of The Local Historian magazine on "Operative Brickmakers in Victorian brickyards" describes the lives of 19th century brickmakers. I used this helpful article to find out a bit more about what Samuel's life as a brickmaker may have been like.

Reputation : The article draws attention to the fact that nineteenth century fiction tends to show brickmakers in a bad light. Dickens for example portrays them as drunken, wife-beating, depraved men in Bleak House and other books. The authors quote a Birmingham brickmaster who is alleged to have described the brickmaking trade as "poor, despised and dirty" in the 1870s-1880s. A factory inspector said in 1873 that "the quantity of beer consumed by "brickies" is almost incredible". I wonder whether Samuel fitted this stereotype ?

"Photo Copyright FreeStockImages.org www.freestockimages.org

Family : Brickyard employees were often recruited as young children. The Local Historian article describes how children would work in the gangs that serviced the skilled brick moulders, carrying clay and moulded bricks to and from the moulder's table, or lead the horse which worked the pugmill, or attending the brick kilns at night. Before the 1871 Factory Act there was no minimum age and even then the Act only made it illegal to employ boys under 10.

George Smith was a brickmaster in the town of Coalville, Leicestershire, who wrote "The Cry of the Children from the Brickyards of England" in 1871. He became nationally known for his campaigns to improve the life of children working in brickyards, on canal boats and gipsy children. Smith has geographical links to Crick where he spent the last five years of his life living in Crick - see www.crick.org.uk/smith.html.

His campaigns against child labour and evidence he supplied to Parliamentary enquiries led to the Factory Act. I have no evidence that Samuel Leatherland started brickmaking as a child, the earliest reference to his occupation is when he was in his mid twenties.

The brick moulder would often use his wife and children to assist in his work. Child labour was not therefore simply the result of evil employers, employees would often choose to involve their family. Brick moulders might be paid according to the number of bricks made, so employing his family would make sense to keep the earnings in the family.

Community : The Browns found that brickyard workers had varied patterns of settlement. Some would be from brickmaking families. Brickyards tended to be small and widely dispersed throughout the country. Transporting large quantities of heavy bricks was difficult, so they tended to serve the surrounding area.

Being migrant workers, the Leatherlands were probably housed in fairly primitive accomodation near the brickfields. The article gives examples of brickmakers living in brickyard huts rather than houses, although some brickmasters did build houses for their workers. Life must have been hard for the family. Their daughter Mary was born in Balcombe in May 1841. It must have been hard for Samuel's wife Elizabeth to give birth in those surroundings, a hundred miles away from the rest of her family.

Work : Brickmaking was seasonal. It tended to cease in the winter, when the weather was harsh and daylight hours restricted. Brickmakers and their family might struggle to make a living, and it is likely that brickmakers would try to find other sources of employment and income. It was hard physical work. It is interesting to note that in his later years Samuel described his occupation (in censuses and on his children's birth certificates and baptism records) as a labourer. This could have reflected a reduced demand for bricks in the area, but it seems equally as likely that he became too old to be a productive brick maker.

Public Perceptions : The article points out that despite the poor reputation of Victorian brickmakers, their social circumstances varied significantly, so the stereotype may not be accurate. Some brickmakers formed colonies of "incomers" / migrants where they were probably viewed with trepidation by locals. But some brickmakers were firmly rooted in their community.

Brickmakers were considered to be relatively well paid during the working season. But this security was temporary and they would often have to find other works at times, for example as a farm labourer. The Browns compare brickmakers who worked in migrant gangs to the railway navvies, who were also viewed with suspicion by the local population.

Edward Leatherland : Weaver

Edward was born in Crick in 1739. The evidence suggests that he lived there for most of his life. His brother William is my direct ancestor.

He married Sarah Palmer when he was 41, quite a late age for a first marriage in those days. He appeared in the 1777 Northants Militia List in Crick as a weaver. There is no evidence that Edward and Sarah ever had children.

There are several family wills which give us glimpses of Edward's life. In 1789 he was an executor and beneficiary of his mother, Esther Leatherland's will. He inherited £10.

Edward made a will himself in 1814 the year before he died. In the will he described himself as a weaver of Crick. He left his house and buildings ("tenements") adjoining the house to Sarah and the rest of his estate to nieces. He made some specific bequests, for example a cream jug was left to a niece.

There was an inventory of his estate with the will. His clothing and purse was valued at £35, household goods and furniture at £32, but there were debts owed to him and "notes of hand" (IOUs) valued at £280. His total estate at probate was valued at £450. So Edward probably died a wealthy man, which was not uncommon for weavers, although we can't be sure that the £280 owed to him was ever recovered. The nieces who inherited this wealth seem to be on his wife's side.

Joseph William Leatherland : Builder in Australia

Joseph William Leatherland is an interesting character. He was the eldest son of William and Jane Leatherland of Kilsby being born five months after they married.

The 1881 census shows that Joseph [named as William] was a 20 year old bricklayer's apprentice living at Osler Street, Birmingham with the Mitchell family. Mr Mitchell was a builder.

Passenger lists of emigrants to Queensland, Australia show that Joseph sailed from London to Brisbane arriving in November 1883. He died of typhoid in 1896 in Johannesburg, South Africa (perhaps on his way back to England ?).

Sydney NSW 1890s

Sydney NSW 1890s

I discovered a series of letters in the Northants Record Office from Joseph's father, his sister Louisa and his brother Samuel to a firm of solicitors CM Roffe in Long Buckby. This correspondence shows that Joseph emigrated to New South Wales, Australia where he worked as a builder. The letters - which date from 1910 - show that the solicitors discovered that Joseph owned some land in Sydney. They refer to a business partner in Sydney, a Mr A Smales. The letters do not mention a wife or children.

I also found a legal announcement in the London Gazette of 12th Feb 1897 regarding his estate. This says that he was formerly a resident of Kingston-upon-Hull and late of Johannesburg, South Africa and that probate of his estate was granted to his father William Leatherland of Kilsby. The reference to Kingston-upon-Hull is a bit of a mystery.

Sarah and Rebekah Leatherland - Sisters who both married the same man !

Two Leatherland sisters both married the same man. This is their story.

Rebekah was Sarah's older sister by 10 years. They were both daughters of William and Jane Leatherland and brought up in Kilsby. Rebekah married a man called Thomas Butler when she was 26 years old. They had five children and settled in Hillmorton, on the outskirts of Rugby.

Sarah's life took a rather different route. She remained single and can be found in 1841 working as a farm servant in Rugby living in the household of a victualler. In 1851 we find her in Dunchurch, another suburb of Rugby, working as a house servant in the family of Benjamin Johnson, a draper and grocer.

Both of their lives changed during the 1850s. Rebekah died in 1854 (there is a record of her burial although the death does not appear to have been registered). Meanwhile her sister Sarah married a Thomas Butler in 1855. Was this just a coincidence ? I don't think so. Various details match so it seems that following Rebekah's death, Thomas married his spinster sister-in-law Sarah.

Marrying in-laws in some circumstances was actually illegal. Until the Deceased Wife`s Sister's Marriage Act of 1907 it was in fact lawful for a man to marry his sister=in-law.

Hannah Leatherland - Hairdresser's Servant in Coventry

Hannah is from the Pailton / Monks Kirby branch (see "The Samuel Leatherland Mystery"). Her baptism has not yet been found, but she was probably born around 1835. She was the youngest of her brothers and sisters. By 1851 she had left home and was working as a domestic servant in the household of John Adrian, a licensed victualler (pub landlord) in Far Gosford Street, Coventry.

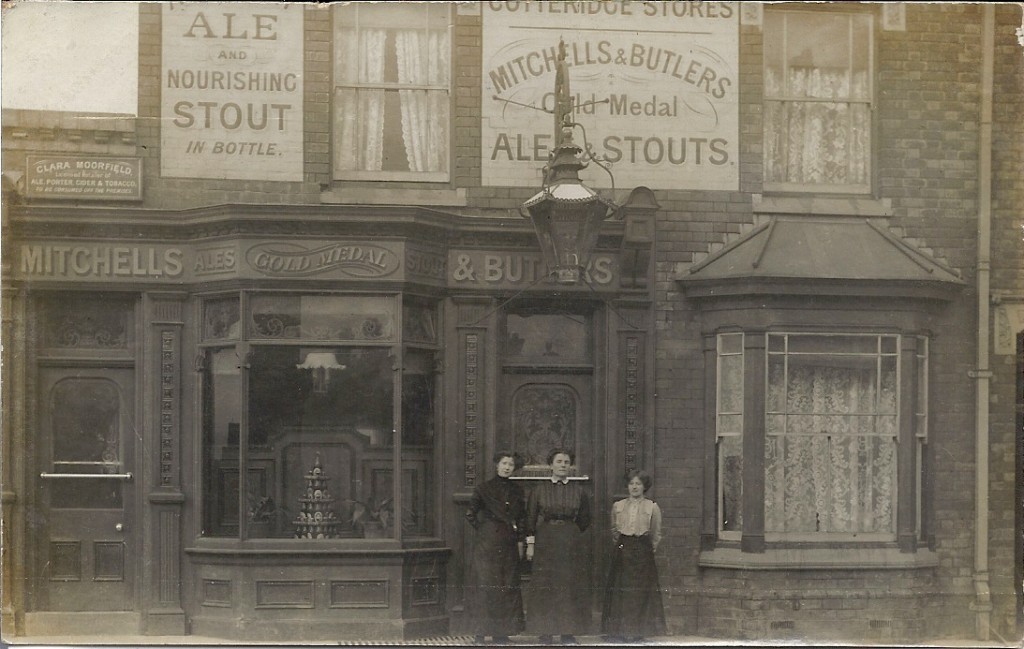

A nineteenth century pub

Hannah seems to have remained in Coventry for most of her life. The 1861 census shows her living with the Dalman family, who were hairdressers, as a general servant. She remained living with the Dalmans as their household servant. By 1891 the Dalmans had retired, but Hannah still lived with them.

John Dalman died in 1900 at age of 83, his wife Ann died three years later aged 91. The 1901 census shows that Hannah was no longer living with them, she was a 66 year old lodger "living on her own means" still in Coventry but now in the household of Elizabeth Mayfield a silk warper. The reference to her living on her own means suggests that she may have inherited money. In his will John Dalman gave Hannah an annuity of £26 per annum.

Hannah never married and there is no evidence that she ever had children. At some point she moved back to the Pailton area - when she died in 1905 she was living or staying at Brockhurst in Monks Kirby.

Hannah left a will, and this will was a crucial piece of evidence in my research. Probate was granted to an Edward Colban, a local schoolmaster, and her estate was valued at £277. That was quite a large sum of money in those days, where did a servant get that money from ?

Who was Edward Colban ?

Edward Colban seems to have been quite a character. According to a post on the Warwick Rootsweb site, there is a booklet about the history of Monks Kirby which explains that the final phase of Monks Kirby Grammar School is identified with the name of Edward Colban, who was appointed headmaster in 1859 and retired in 1912 at the age of 73.

Edward Colban was a teacher from Battersea College who was appointed headmaster at a salary of £65 pa. Colban is described as follows : "a teacher of outstanding ability and a strict disciplinarian. Headmaster for over 52 years, in a number of cases he taught three generations of the same family. He was a "character" and in later years became somewhat autocratic. Standards declined and a visit by HM Inspectors in 1894 produced a critical report, so that a new committee under Lord Denbigh had to fight hard for the schools survival .Meanwhile two other schools had come into existence which continue to serve the village and its neighbourhood to the present day. . . . . .. In 1912 the old grammer school was amalgated with Brockhurst to form a mixed C of E school in new premises. The old grammar school, enlarged is now the Village Hall. Old Mr Colban resisted to the end and "absolutely refused to accept a pension of £60 a year". He was eventually given £100 pension, and the house for the rest of his life, and is remembered with affection and respect by the older inhabitants. "

[This post can be found at www.mail-archive.com/warwick-l@rootsweb.com/msg02477.html ]

Alfred Leatherland : Lamplighter

Alfred was the grandson of Samuel Leatherland of Kilsby (1810-1894) via Samuel's second marriage to Sarah Whiteman. His father, Henry was a policeman in Northampton rising to the rank of Inspector before his death from cancer at the age of 49.

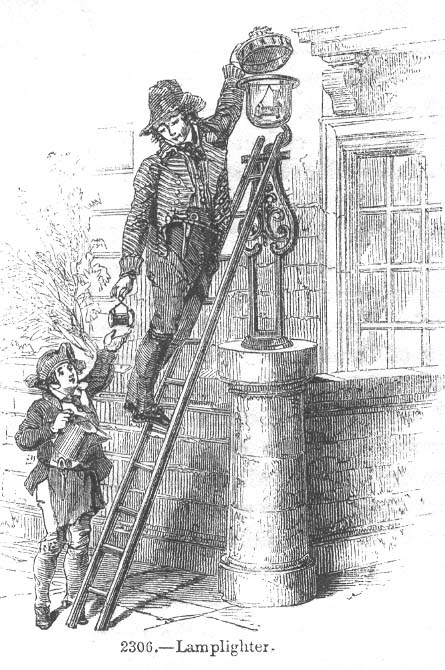

Alfred was born in Kilsby in 1888, so he would have known his grandfather as a boy. By 1891 his parents had moved to Northampton. The 1911 census shows 22 year old Alfred working as a lamplighter for a gas company. Three years earlier he married Annie Whiting and they had three children.

Lamplighters were employed to light street lights, usually by a wick at the end of a long pole. At dawn, they would return and turn them off using a small hook on the pole. Early street lights were generally candles, oil, or solid lighting sources with wicks. Lamplighters also carried ladders so that they could renew the candles, oil, or gas mantles. In some communities, lamplighters served in the role of a sort of town watchman. In the 19th century gas lights became the dominant form of street lighting. Early gaslights required lamplighters, but eventually systems were developed which allowed the lights to operate automatically.

Alan Clarke's Northants family history website www.northants1841.fsnet.co.uk includes excerpts from reminisences by Northampton residents Bob Stanton, Len Riley and Jim Allard :

Bob Stanton remembered Mr. Perrin the lamplighter who lived on the Mayorhold (an area of Northampton), in the sweet shop :

"Mr. Perrin was the lamplighter and when he came out with his long pole, that was the signal to out and close the shutters and then start getting ready for bed. A lot of houses had shutters which were like two small doors that closed across the windows. They made the room very cosy in the winter - as good as double glazing."

Len Riley : "We used to play him up! There was only one lamp in Herbert Street and one at the top - and as soon as he'd lit the lamp we'd shin up the lamp-post and blow it out. He used to have a long pole what he kept for light but it was shielded so that it didn't go out. He used to push up the glass trap door like, and turn the gas on with a hook and light the gas. He used to spend his daytimes going round these lamp-posts, climbing up and cleaning them, washing them all down. It was a full time job for him."

Jim Allard : "We used to follow him about. And I said, "Hooray!" every time he lit a lamp."

My grandfather who grew up in Birmingham in the 1900s remembered chatting to the local lamplighter who was the first person to tell him about socialism.

Alfred Leatherland died when he was 42. The National Probate Calendar shows that he left an estate of £227 and 18 shillings.

Contact me : David Richards E-mail : davidr4u@btinternet.com