Kilsby Leatherlands

Kilsby is a compact village about 15 - 20 minutes drive south east of Rugby along Kilsby Lane. It lies to the east of the Northampton to Rugby railway line and the M1.

Kilsby's history has been well documented by the late Gren Hatton in print and on the Heritage and History pages of www.kilsbyvillage.co.uk. His comprehensive village history "Kilsby The Story of a Village" is excellent. Hatton also produced a fascinating book "At That Particular Time" containing recollections and anecdotes from elderly residents of Kilsby. My brief description of the village history relies heavily on these works.

Kilsby

Kilsby has Roman origins. Traces of Roman settlements have been found during archeological excavations together with fragments of Roman pottery. The Roman road, Watling Street, runs close to the village and the Kilsby stretch of Watling Street is still a public right of way marking the border between Kilsby and Crick.

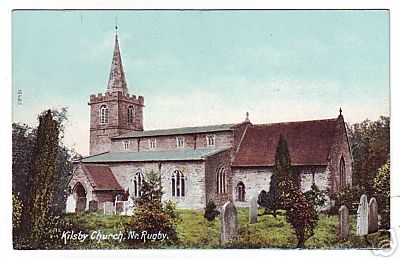

Kilsby as a village was probably founded around 900 AD. The name probably has Saxon and Danish origins. There are still traces of medieval Kilsby in ridge and furrow field patterns, windmill mounds, and the parish church, St Faiths, which was built in the fourteenth century.

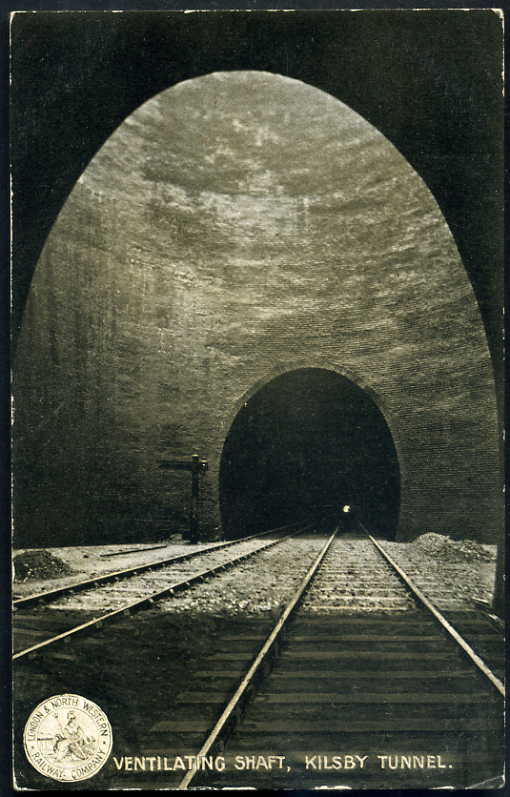

Kilsby has two particular historical claims to fame : the first fighting in the English Civil War began there in 1642 and the Kilsby railway tunnel built in the 1830s which formed a key section of the world's first inter- city railway, the London to Birmingham line, which, when built, was the longest tunnel in the world.

From the late 17th century to the late 18th century Kilsby was dominated by the cloth weaving industry. Weaving was carried out on hand looms in cottages. Gren Hatton estimated that there were fifty to seventy handlooms at work in the village, along with support workers such as woolcombers (who washed, cleaned and combed the wool to prepare it for spinning), spinners and carpenters (who built and repaired the handlooms). A number of families prospered and some became merchants of such standing that they were able to issue their own trading tokens. A history of the 1720s stated that Kilsby comprised seventy two houses, nine of which were set aside for the poor. A later history records 148 houses in 1801, with 703 inhabitants.

Kilsby's prosperity declined in the later 18th and 19th century. Gren Hatton explains that its textile industry was destroyed by :

- The Industrial Revolution which created machines and factories that were much more efficient than cottage hand-looms and undercut their prices.

- The enclosure of Kilsby's open fields in 1778 which impoverished many villagers (but made some farmers richer).

- The Napoleonic Wars between England and France from 1799 to 1815 which meant that many workers had to serve in the army and led to economic depression because of the need to pay for the wars.

The 1847 Post Office Directory said that Kilsby had a population of 655 in 1841 and an acreage of 2,227. Nineteenth century directories invariably describe local charities and Kilsby had charities with an annual value of £18 "laid out in money, bread and educating the poor".

The directory lists three local gentry, plus ten farmers (five of whom were from the Cowley family), three butchers, two millers, three bakers, two blacksmiths, two shopkeepers, one carrier (who also ran the Devon Ox pub), two farmers who were also cattle dealers, one cattle dealer, two farmers and graziers from the Cowley family, two farmers and graziers from the Lee family, one plumber and glazier, Mrs Jeziah Essen who ran the Post Office and was also a butcher, two pub owners (including Samuel Frisby of the Red Lion who we meet elsewhere on this site), two surgeons, two carpenters, a railway contractor, a road surveyor, a saddler, two beer retailers, a tailor, a bricklayer, four shoemakers, a wheelwright, and a baker.

Kelly's Directory of 1890 gives a vivid description of Kilsby village at that time as well as listing "private residents" (local gentry / landowners) and commercial traders. Kilsby's soil was strong loam", with the subsoil being clay and gravel. The chief crops were "wheat, barley and oats". The main landowners were the Cowley family and the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. We learn that the National School had an average attendance of 120 pupils and that the master (headmaster) was William Postle. Kilsby railway station's stationmaster was Jabez Shrives.

One of the main purposes of Kelly's Directory was to give useful information about communications between towns and villages. The Kilsby entry tells us that letters could be posted up to 8.30 pm and that there was a daily delivery of post at 7 am. The Directory also lists the village carrier, Thomas Haynes, who provided carrier services to Daventry and Rugby twice a week (especially on Saturdays), and to Lutterworth as an occasional Thursday service.

William Leatherland is included in the list of commercial traders as a thatcher.

Kilsby Leatherlands

My ninetheenth century ancestors began with William who married firstly Ann Hall and then, following her death, Jane Daniel in 1803.

William Leatherland married Jane in Kilsby Independent Chapel in 1803. He was a widower. The Bishop's Transcripts show his previous marriage to Ann Hall who died in 1801. I don't know much about Jane. She was probably born around 1780. Her age was given as 69 on her 1841 death certificate but the informant was Mary Bateman who was probably a neighbour and may not therefore have known how old she was (do you know your neighbours' exact ages ?!). In the 1841 census Jane said she was 60. I have not found Jane's baptism in the Northants parish register indexes, although she said she was born in Northants.

Hunt's House, Kilsby. Parts of the building date from the 15th century although most of the stonework is 17th century.

William and Jane had nine children all baptised in the Kilsby Independent Chapel. They had mixed fortunes.

- Mary died when she was 21. That's about all I know about her.

- Rebecca married Thomas Butler in Hillmorton, a suburb of Rugby, when she was 26. The censuses show that they settled there and had five children. Rebecca died in 1854. Her husband later married his late wife's sister Sarah.

- John was born in 1807. He married twice, firstly to Susanna Emery in 1833. A year after her death in 1853, he married Elizabeth Frisby. I have not found any children of either marriage. Both Frisby and Emery are names which crop up often in Kilsby history.

- Samuel was next. He was born in 1810 in Kilsby and baptised the following year in Kilsby Independent Chapel. When he was 25 years old, he married Elizabeth Crofts in Churchover, the bride's home village. Elizabeth was 18 years old when she married.

- Jane, the next child, was born in 1812. She died when she was 23.

The Story of Fanny Walden

Hannah, the next child, was two years younger than Jane. She was another one who married twice following the death of her first husband, John Walden. She settled in Rugby with her second husband William Swingler who worked as a "boysman" at Rugby School. Hannah also had a child, Fanny, three years before she first married.

Fanny's story is rather intriguing. We don't know who her father was. In the 1851 census she was an 11 year old in Crick living as a lodger with her aunt and uncle John and Susannah Leatherland, her mother Hannah Walden and her brother Charles Walden. In 1871 she was an unmarried dressmaker living in Railway Terrace, Rugby, with mother (now Hannah Swingler) and step-father William Swingler.

Her mother died in 1878. Fanny remained living with her step-father in Rugby. Then in 1881 William Swingler and Fanny got married in Coventry. Fanny was in fact only nine years younger than William. Fanny died in 1896. William lived until 1916.